I'd forgotten that acting is, like, hard.

Here is a Letter from the Homestead recapping May. Inside: I acted in a play. It was hard. So, I made a list of promises to uphold as a playwright to actors.

Emily Dickinson called her Amherst home “The Homestead.” I lovingly call my apartment in St. Louis the same thing (though I definitely get out more than Dickinson). This monthly newsletter is my attempt to work through what it feels like to put down roots as a writer in my own Homestead.

Acting is really hard. I’d forgotten.

This past month, I was rehearsing and then opened The Heidi Chronicles by Wendy Wasserstein at New Jewish Theatre in St. Louis. It’s been years since I was in a professional play— the only times I’ve been on stage recently are in prison plays with the artists I work with at Prison Performing Arts. In those plays, I’m usually sweating too hard to be thinking about “the acting.” I’m just trying to talk loud enough and hide my sweat stains.

But “realistic” acting in a traditional theatre play is hard, y’all. It’s really hard. I’d forgotten how hard, and I’m ashamed.

After this most recent experience, I kinda believe all playwrights ought to act in a play regularly, and I think a requirement should be that it isn’t one they’ve written.

I’ve learned a lot about plays while being in The Heidi Chronicles these past several weeks. Maybe the biggest “learning” is that I’m not equipped to write a far-reaching, episodic play like this one. (The Heidi Chronicles follows one woman, Heidi Holland, from 1965 to 1989.) This play is also firmly grounded in realism, which is not how my own plays come out. But I think it’s really good for me to live in a play like this for a while, one that’s so different from anything I would create myself.

(Being in a play has also reminded me that I’m a mouth-breather onstage and that this is bad. It really dries you out.)

When you’re a playwright in a play, you get to physicalize what you so often ask of actors. Suddenly, you’re doing super quick costume changes because the playwright decided your track needed to play back-to-back scenes with a 15 second break. And you realize that the playwright maybe didn’t think it through…

I like The Heidi Chronicles. I think Wendy Wasserstein asks some good questions about what a “happy life” entails, and she writes a strong villain (a charismatic creep) who still interests us today. Full disclosure, though— I think Wendy would hate a Courtney Bailey play. Too much of a silly goose, she’d say. Too afraid of realism for her own good, she’d add.

She’d be right.

We’re different playwrights. Different educations. Different interests. Different generations, too. And I’ll never have the success of Wendy Wasserstein, which suits me okay. I can pay my bills.

Different plays asks different things of actors. The process for The Heidi Chronicles has got me thinking about my own “rules of engagement.” I’m a people-pleaser by nature (big downfall, honestly), and the people I want to please are my friends (who are mostly actors), and so I guess that means I write actor-centered plays. I don’t think all plays all actor-centered— some center on ideas, a single character, the playwright’s ego, or just really pretty words. Maybe every playwright has personal rules of engagement.

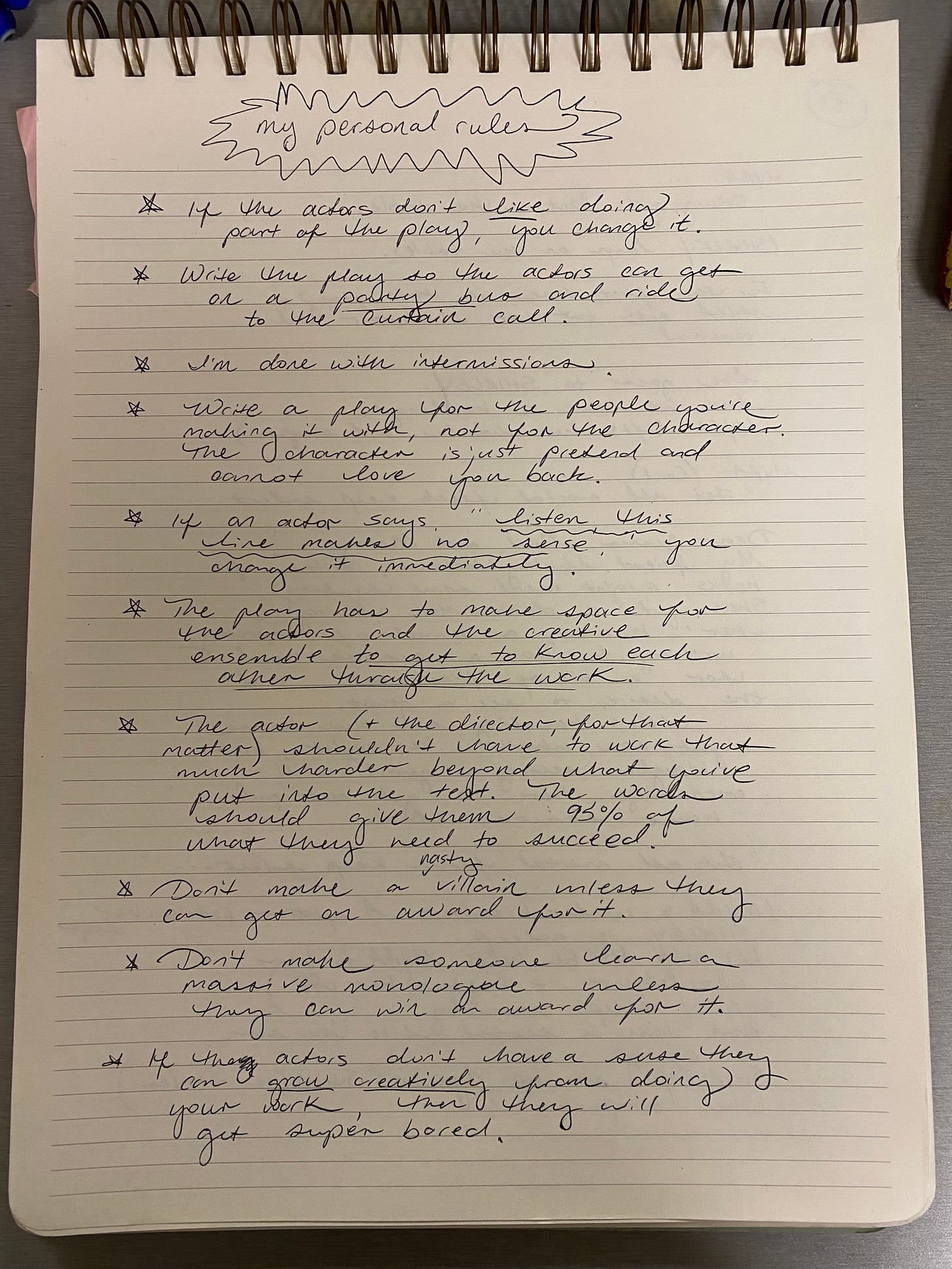

In the dressing room during one of our matinees, I made my own list.

my personal rules for an actor-centered play:

If the actors don’t like doing part of the play, you change it. This is assuming the actors you’ve found to graciously do your play are people you love and respect. You should trust them. You are just a playwright, not god. Now, if they don’t like doing the entire play, you need to recalibrate entirely. How did you get this far anyway?

Write the play so the actors can get on a party bus and ride to the curtain call. A play is not an easy thing to do, but there are things you can finesse to make the ride easier: a sense of balance with the characters, snacks, speed, opportunities to sit down, etc. I like to see actors being courageous and showing off their skill, but it should be a party while they’re doing it, not a chore. They should enjoy the work. I distrust martyr-actors, and I kinda think they hate themselves.

I’m done with intermissions. These days, they take me out of it. And as an actor in this particular play, they really take me out of it. I want to write the party bus play where you can just ride to the end. I promise to do everything I can to write 80-90 minute plays with ZERO need for an intermission.

Write a play for the people you’re making it with, not for the characters. The characters are just pretend and cannot love you back. Because the work I make starts like a group project, I’m much more interested in the people in the room than the characters themselves. The characters are fun but fake. Yes, I am totally aware that most playwrights are trained to focus their energy on building the text, and that’s amazing, but, these days, I can’t wait to get finished with the writing part so I can get to the community part. That’s what motivates me (and I know it does not motivate all playwrights—remember, these are my personal rules.)

If an actor says, “listen, this line makes no sense,” you change it immediately. I am too tired to argue with the actor who is going to have to say the line a zillion times. And they are almost certainly right.

The play has to make space for the actors and the creative ensemble to get to know each other through the work. An interesting thing about The Heidi Chronicles is that it seems to be written as a “gift” for the actor playing Heidi, but then it keeps her onstage the entire time and doesn’t really let her hang out with any of her fun castmates backstage! In doing so, this performer has to work so hard that they become siloed from the other actors who have way easier tracks. Yes, the performer (and, listen, our Heidi is killing it) gets her flowers every night, but she gets no time to kick back and chill with the team. As a playwright, this makes me sad! I want everyone to have a chance to get to know each other (if they wish, of course).

The actor (and the director, for that matter) shouldn’t have to work that much harder beyond what you’ve put into the text. The words should give them 95% of what they need to succeed. I promise to not show up to a play reading without doing my best to make sure the play is as good as I can possibly get it on my end first. I never want to have the mindset of, “Oh, so and so will fill in the blanks here on this comedy bit or this moment because I’m too lazy.” I promise to always do that work first, and then trust the process if it needs to be revised in rehearsal.

Don’t make a nasty villain unless they can get an award for it. Speaks for itself.

Don’t make someone learn a massive monologue unless they can win an award for it. Also speaks for itself. Don’t make someone work unless there’s a prize!

If the actors don’t have a sense that they can grow creatively from doing your work, then they will get super bored. My friend Joel, who plays Scoop Rosenbaum in The Heidi Chronicles, was telling me about how he turned down another role to play Scoop, saying that he suspected our project would be more artistically fulfilling. It got me thinking about how this is a good goal for a playwright: Is the play I’m writing going to be artistically satisfying for the actors? For the director? The designers?

I wonder how I’ll feel about these “promises” in five years or so. I’m sure there are playwrights out there (likely some of my colleagues) who find these promises ridiculous or even “groveling” to actors. But I do sort of worship at the actor’s feet, you know? They are the ones who grant me the grace of seeing the dreams I’ve planned danced out— over and over and over again. That is a grace, and for it, yes, I will grovel.

What I’m reading this month…

A Change of Habit by Sister Monica Clare. I love a nun memoir. This is a funny, southern nun memoir. Very good.

The Art Spirit by Robert Henri. I was assigned this book in design class in college. I come back to it regularly. I’ve been dipping into it while working on The Heidi Chronicles.

The Mystics Would Like A Word by Shannon K. Evans. This is a tremendous overview of several women mystics, many of which I learned about during my English PhD but never dug into that deeply. I was especially impressed with the chapters on the medieval memoirist (literally the first!) Margery Kempe.

100 Essays I don’t have time to write by Sarah Ruhl. I went picking through this book of essays this month looking for ideas for my writing workshop and found myself sitting down to read. So many good reflections. I love what she has to say about people sleeping during her plays (what wonderful dreams they must have!).

How I made money this month $$$

I believe freelance artists should be more upfront about how they support themselves financially, rather than maintaining the illusion they are fully supported by their art (they usually aren’t). This is me attempting to live out that principle. So, here are all the ways I brought in money to the Homestead for the month of May.

Teaching artist work for Prison Performing Arts. Teaching a weekly writing workshop on Zoom and teaching Spoken Word regularly for two men’s prisons.

Paid Substack subscriptions. Thank you to all of my paid subscribers. It means the world to me you make a financial contribution to my work.

Happy Pride Month! 🏳️🌈 I adopted another cat. Here he is. His name is Francis. Midge is displeased.

Thank you, as always, for reading and supporting my work.

Yours,

Courtney xoxo